Up: democratization-autocratization

Esen, Berk, and Sebnem Gumuscu. 2021. “Why Did Turkish Democracy Collapse? A Political Economy Account of AKP’s Authoritarianism.” Party Politics 27(6): 1075–91. doi:10.1177/1354068820923722.

robert-dahl’s (1971) analytical framework of cost-of-toleration-and-suppression

- How partisan redistribution serves asa casual mechanism that alters the cost of losing power for both the ruling elite and their supporters. In turn, the cost of suppression is lowered for the ruling elite.

- Why winners of democratic politics end up undermining it?

- The casual mechanism behind democratic collapse is the “partisan redistribution” of resources to coalition partners in an increasingly corrupt manner, which entails “reallocation” of favors and clientelistic goods from former beneficiaries to pro-AKP businessmen and urban poor. Incumbents’ fear of retribution and prosecution increases their cost of losing power through free and fair elections. Their clients also fear change of government because they receive favors via partisan redistribution, and they presume that government change could result in loss of such resources to tother social groups. Hence, their “fear of future redistribution” of their current benefits under AKP government drives their cost of toleration up. This collective aversion of the ruling elite and their clients has consolidated the party base around mutual interests, and this popular support substantially reduced AKP leaders’ cost of suppression.

- In agreement with Waldner and Lust (2018: 109), we posit that shifts in cost of toleration and suppression provide a casual mechanism that accounts for why freely elected governments start to undermine democratic politics often with tacit or explicit popular support.

- It is not the socioeconomic elites that conspire against democracy (i.e. losers) with armed forces as they suggest. Instead, it is the democratically elected government and their partisan clients who benefit from government’s policies that undermine democracy for they fear the loss of their privileges once the government changes hands.

- Our account offers a casual mechanism for democratic backsliding at the hands of popularly elected leaders.

- Coalitions that undermine democracy cut across class lines and bring together different socioeconomic groups.

- Different social groups with democratic attitudes can end up supporting an authoritarian party once they grow dependent on the government.

Is Turkey a case of democratic backsliding or breakdown?

- Turkish democracy was not consolidated before the AKP either. Tutelary powers of the military and the Kemalist bureaucracy — including the judiciary — in previous decades posed the primary obstacle before democratic consolidation (Özbudun, 2000). And yet, the political playing field was mostly even; elections were free and fair, and there were no major inequalities when it came to parties’ access to resources. The “bounded uncertainty” of democratic rule was well established, even if the bounds had been delineated rather narrowly.

- When the AKP came to power in 2002, Turkey was therefore an electoral democracy.

- Backsliding (2007 — 2015)

- The AKP’s violations of civil liberties, began as early as its second term in office (2007 — 2011). During these initial years, although the political system remained open, incumbents targeted specific groups such as Kurdish nationalists, leftist groups, and ultra-secularists while they politicized the bureaucracy and the judiciary (Özbudun, 2015) and built a pro-government media with the organizational help of the Gülen movement.

- After 2010, however, government repression devoured mainstream opposition parties, civil society, and ordinary citizens who mobilized against the AKP rule.

- Since 2011, the AKP amassed power, eroded checks and balances to capture state institutions, and monopolized power in the hands of its leader (Öniş, 2015).

- Electoral playing field tilted in favor of the AKP eroding the competitiveness of elections and rendering each election since 2011 less competitive than the preceding one.

- Breakdown (2015 — present)

- This prolonged backsliding eventually culminated in democratic breakdown in a series of developments following

- the June 2015 parliamentary elections: the AKP government refused to step down despite losing its parliamentary majority in June and called for snap elections in November,

- established emergency rule after 2016 coup attempt and President Erdoğan ruled by decree for 2 years, cracked down on dissent and curtailed political rights,

- and finally, replaced the parliamentary system with executive presidency with weak checks and balances through a referandum in 2017 carried out under emergency rule.

- 2019 → On the election night, the party refused to concede defeat in Istanbul — the economic bastion of the country and major source of clientelist relations; pressured the electoral commission to cancel the elections and secured a rerun on flimsy legal ground — all signs of a competitive authoritarian regime in action.

- This prolonged backsliding eventually culminated in democratic breakdown in a series of developments following

Defining the puzzle: Turkey as a theory-upending case

- Turkey’s recent authoritarian turn under the AKP is highly puzzling: it is a middle-income country with strong ties to the West.

- Structural conditions that are that are conducive to democratic consolidation:

- limited natural resources,

- weak landowning class,

- strong state legacy.

- Turkey’s recent drift into authoritarianism directly challenges the primary tenets of modernization theory.

- Turkey’s backsliding into a competitive authoritarian regime has occurred concurrently with Turkey’s accession talks with the EU, thereby challenging the Europeanization literature.

- The policies of Merkel and Sarkozy governments, not to mention the EU’s critical stance toward Turkey on the Cyprus issue, have weakened the Eu’s leverage over the AKP government as well as the Turkish public support for EU membership (Yılmaz, 2016).

Why do democracies break down?

- Turkey has held relatively strong political institutions, including its century-old parliament and history of holding elections without any significant fraud. Thanks to its parliamentary system, Turkey has also managed to avoid “perils of presidentialism,” which inflates the probability of breakdown (Linz, 1990).

- Neither the theory of weak party systems, nor the rise of personalistic leaders can account for democratic collapse in Turkey. Although the AKP’s meteoric rise occurred against the erosion of support for centrist parties amid 2001 economic crisis, the AKP initially adopted moderate policies and presented itself as a centrist party (Özbudun, 2006).

- Alternatively, cultural factors such as weak civic attitudes, self-expressive values, and low levels of social capital could trigger democratic breakdown. However, the civic culture in Turkey has not regressed over the past decade; in fact, both urbanization and literacy rates have increased in this period. Turkey has a vibrant civil society with close ties to Europe as demonstrated during the Gezi protests in 2013. Support for democracy has been consistently high in the country, and the appeal of radical Islamism has declined over the years.

- Other scholars have focused on supply-side theories:

- Indeed, one could attribute Turkey’s democratic collapse to President Erdoğan’s authoritarian tendencies. And yet, although democracies are often threatened by autocratic leaders, they rarely collapse. Conditions under which such leaders succeed in cases such as Turkey prove to be crucial.

- Other scholars have focused on supply-side theories:

Triangular Dependency and democratic breakdown

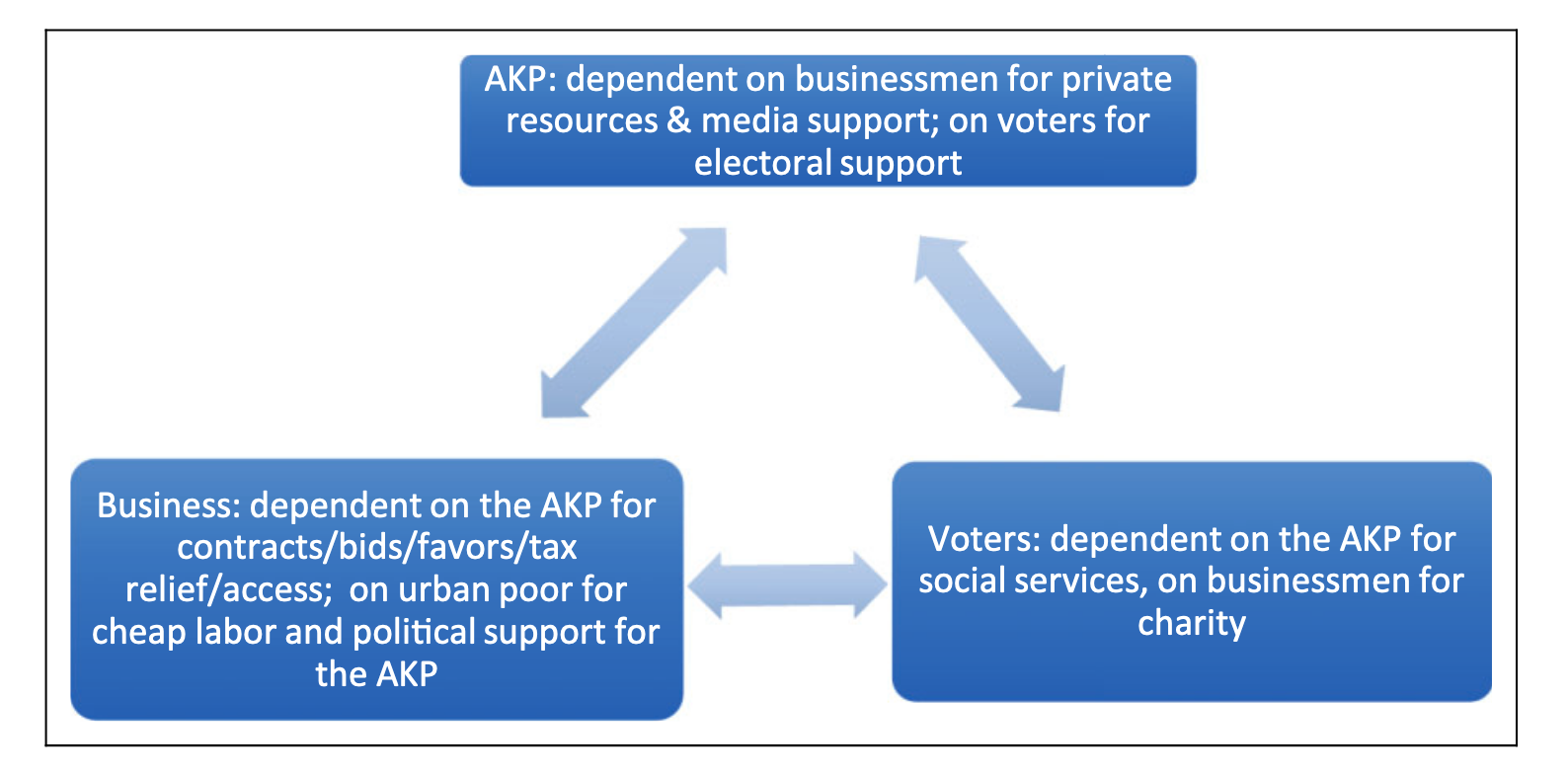

- At the root of the AKP’s democratic backsliding lays extensive capital accumulation and resource allocation for a cross-class coalition composed by the rising economic elite and the urban poor, respectively.

- Economic liberalization of the 1980s empowered a new group of pious Muslim businessmen (Buğra, 1999) while exposing urban poor to increasing precarity (Gülalp, 2001; Öniş, 1997). The Islamic parties mobilized these social groups against the so-called ruling coalition of secular upper and middle classes around secular-Islamic cleavage (Eligür, 2010).

- AKP solidified a cross-class coalition informed by economic interest as well as sociocultural identities, that of Sunni Muslims of Turkish and Kurdish ethnic origins. AKP’s conservative-nationalist worldview that draws on Islamic sentiments and Turkish nationalism served as the ideational cement of this coalition and reconciled potential intra-class conflicts within (Tuğal, 2009).

- As the AKP’s cost of toleration of opposition increases, the party takes steps to undermine the competitiveness of the regime and decreases the “bounded uncertainty” inherent to democracy. As it secures its constituency’s support for its repressive actions, the cost of suppression declines along with AKP’s democratic accountability. Consequently, the AKP can further undermine competitive elections, persecute the opposition, and systematically violate civil liberties without much political cost.